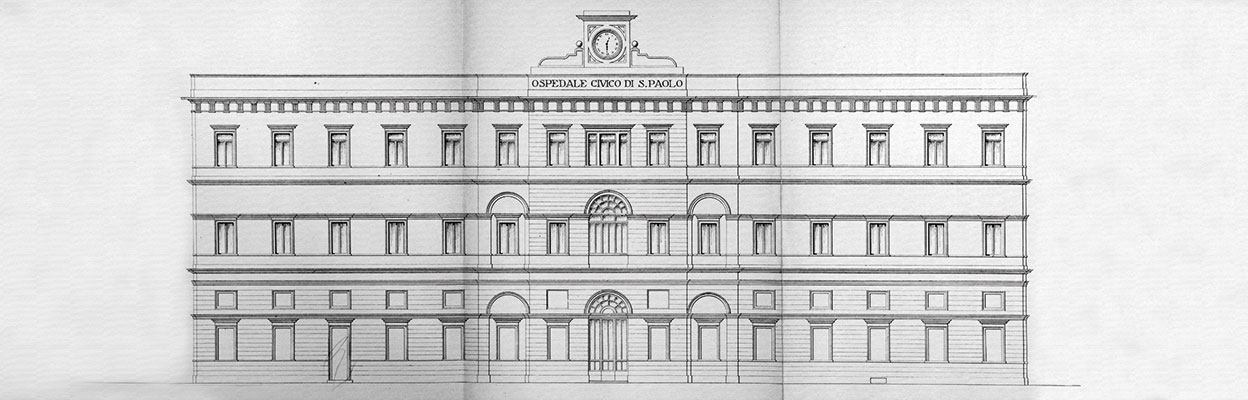

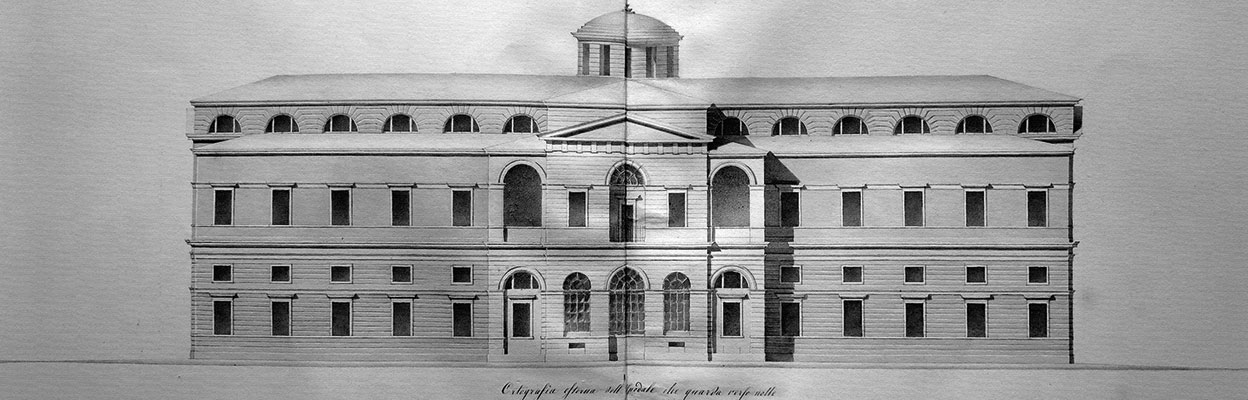

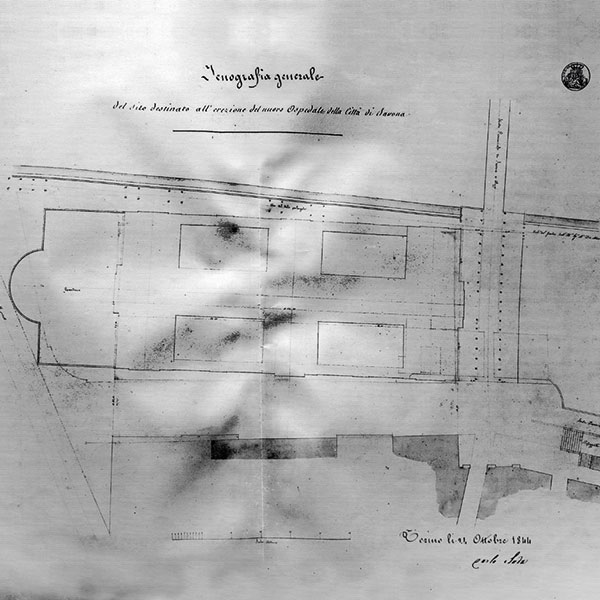

The architect Carlo Sada (Bellagio, 14th May 1809 - Milan, 31st August 1873), thanks to his training at the celebrated Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées, in 1842 at the age of 33, was one of 21 competitors to take part in the competition for designing a "New Public Hospital" in Savona. On 22nd December 1843, the Congresso dei Ponti e Strade di Torino (Congress of Bridges and Roads of Turin) proclaimed Sada as the winner. Continued criticism and second thoughts forced Sada to submit a redimensioned and less ambitious project on 29th January 1846. Yet it was ultimately a dispatch from the King dated 3rd August 1846 that ordered the beginning of the works in line with the initial project. The building was constructed between 1847 and 1856 under the guidance of the Civic Engineer Giuseppe Cortese.

It was then inaugurated on 14th October 1857. 15 long years had passed before Sada's designs gave life to a masterpiece of 19th-century civil architecture. Indeed, at the foot of Sada's tomb lies a little angel, curious and attentive, on the very designs of the Ospedale di Savona.

It was then inaugurated on 14th October 1857. 15 long years had passed before Sada's designs gave life to a masterpiece of 19th-century civil architecture. Indeed, at the foot of Sada's tomb lies a little angel, curious and attentive, on the very designs of the Ospedale di Savona.

As soon as it was completed, the San Paolo building stood out thanks to all its symbolic meaning.

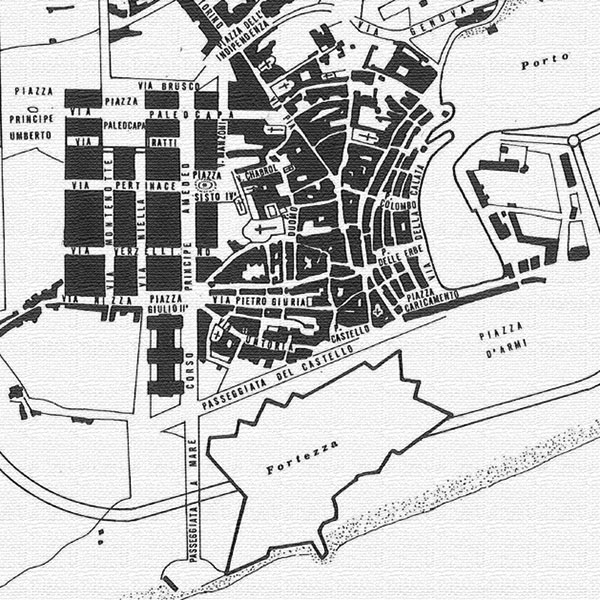

The old city no longer had the space available to meet the needs of the rapidly-changing world under the pressure of the industrial revolution.

Savona perceived the ineluctability of this future and sought to take pre-emptive action. It was necessary to open up to the outside, both physically and in a broader sense. Building began of a public building that would be one of the largest and most modern in the Sardinian Kingdom, bold and clearly oversized for the needs of the time, but also performing the first successful urban expansion whilst remaining extremely liveable, perfect for life in the city.

The keystones of urban expansion were delineated, linking the old city with the symbols of technological and social progress "beyond the city walls": the railway and the new hospital.

THIS IS EVIDENT IN THE WAY THAT THE GEOMETRY OF THE ENTIRE CITY FABRIC WAS DICTATED BY THE DIMENSIONS AND THE ORIENTATION OF SAN PAOLO.

To show the broader importance of the pathways, arcades were competed by obtaining the perspective effect typical of the new cities of the time. On today's Corso Italia, geometric rows of trees will be planted in the location of the porticoes.

To show the broader importance of the pathways, arcades were competed by obtaining the perspective effect typical of the new cities of the time. On today's Corso Italia, geometric rows of trees will be planted in the location of the porticoes.

By 1880, only 23 years since the inauguration of the new hospital, the 19th-century city had taken on considerable consistency even if the axis of Via Paleocapa still did not reach the Torretta and the sea.

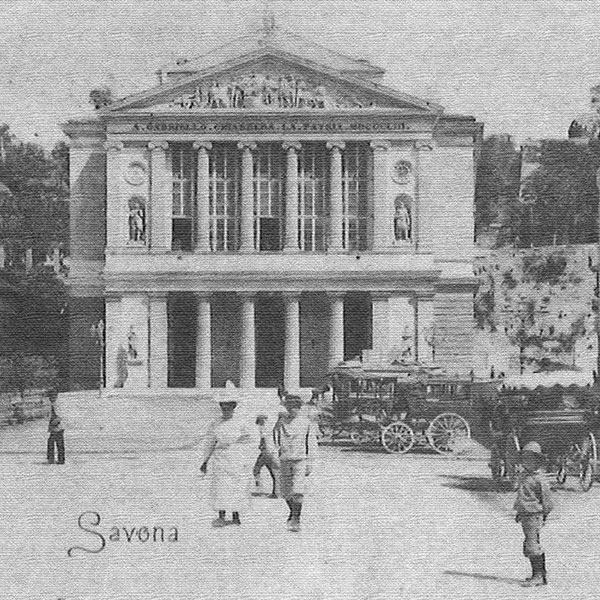

Construction of Teatro Chiabrera, another building that symbolised a society and an era, began in November 1850, concluding three years later with a neoclassical design by the architect Carlo Falconieri of Messina. The Railway Station building, also in neoclassical style, was built in 1881.

WITH THE GEOMETRIC PERSPECTIVES, ITS NEOCLASSIC PUBLIC BUILDINGS, THE TREE-LINED AVENUES, PORTICOES AND GARDENS, 18TH-CENTURY SAVONA PROVED TO BE KEEPING UP WITH THE TIMES.

Like the big European capitals, it too underwent a phase of demolitions for "reasons of hygiene" which, in the face of lavish expropriations, permitted the opening of new wide and regular roads that strengthened the perspective perception of the city and consolidated its modern organisation that is still perfectly efficient today. Between 1880 and 1910, the road between Piazza Giulio and La Darsena was built in this way, as had happened a few years prior for Via Paleocapa. The creative process of the "orthogonal city" that had started with the construction of the San Paolo was now complete.

Like the big European capitals, it too underwent a phase of demolitions for "reasons of hygiene" which, in the face of lavish expropriations, permitted the opening of new wide and regular roads that strengthened the perspective perception of the city and consolidated its modern organisation that is still perfectly efficient today. Between 1880 and 1910, the road between Piazza Giulio and La Darsena was built in this way, as had happened a few years prior for Via Paleocapa. The creative process of the "orthogonal city" that had started with the construction of the San Paolo was now complete.

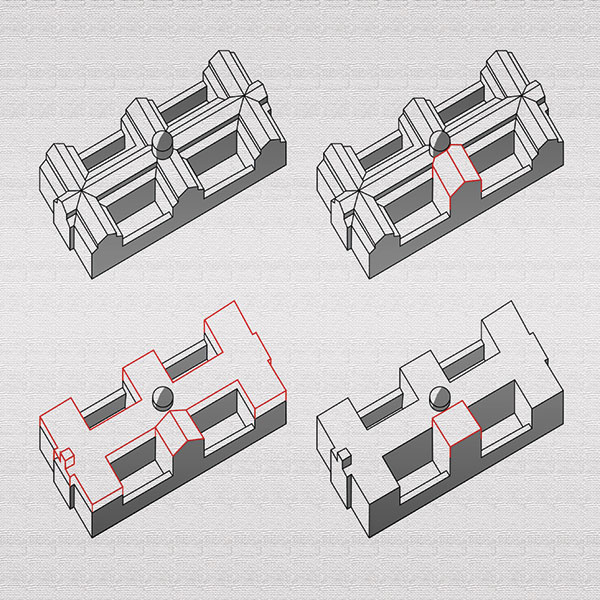

Although conceived as a hospital, the rationality and modularity of Sada's project allowed the building to be adapted to suit multiple uses and to surprise thanks to the potential for modification and expansion with which to meet new needs. The first function hosted by the hospital was that of a kindergarten that operated for around 17 years as of 1854, even before the inauguration, until 1871.

At the same time, there was also a design school and, from 1868 until the early 1900s, the Pinacoteca Civica. The quality and solidity of the original construction would prove to be a precious resource in overcoming the progressive lack of space linked to the evolution of the hospital structure. The generous walls of the ground floor and the technology of the foundations, in fact, permitted the heightening of the entire building that occurred in successive phases.

An initial and partial operation concerning the only central transversal body facing Via Giacchero was carried out between 1905 and 1908. The raising of a floor of the entire building was undertaken between 1928 and 1931 based on the modern and bold project of Engineer Damonte that, whilst relying on the new potential of reinforced concrete, consolidated the neoclassical setting and the initial monumentality, resulting in the sober and harmonious building of today.

In early January 1991, the healthcare activities were definitively transferred to the new headquarters in Valloria. After having served its purpose for 134 years, the building could no longer adequately respond to the needs of the ever-changing hospital organisation.

In early January 1991, the healthcare activities were definitively transferred to the new headquarters in Valloria. After having served its purpose for 134 years, the building could no longer adequately respond to the needs of the ever-changing hospital organisation.

IN JULY 2003, THE DESIGNS OF THE CATALAN ARCHITECT RICARDO BOFILL WERE PRESENTED, THE EXPRESSIVE STRENGTH OF WHICH SUCCEEDED TO COMMUNICATE AN EXCITING VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF SAN PAOLO.

A long period of inactivity began for the "Old Hospital" at the end of which the owners (the Municipality and Health Authority) put it up for sale, with the buyer having the obligation to completely restore the building and, once the works are completed, to return a portion to the institutions that were the originally owners. On 4th July 2003 (161 years after the first tender for the construction in which Sada took part) a tender was announced for the selection of a buyer who, in addition to the most advantageous offer, had to present a project with a plan for restoration and future use. Along with the offer that would go on to be judged the best, the designs of the Catalan architect of Barcelona, Ricardo Bofill, were presented, with an expressive strength able to communicate an exciting vision for the future of San Paolo, comprised of openings, light, transparencies and new life dictating the guidelines of the project developments that were to come.